The Gay Divorcee

| The Gay Divorcee | |

|---|---|

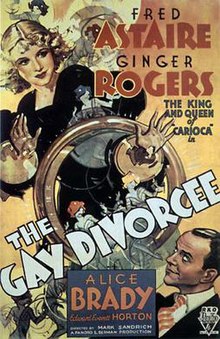

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Mark Sandrich |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Based on | Gay Divorce 1932 musical by Dwight Taylor |

| Produced by | Pandro S. Berman |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | David Abel |

| Edited by | William Hamilton |

| Music by | Score: Max Steiner Songs: (see below) |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | RKO Radio Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 107 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $520,000[1] |

| Box office | $1.8 million[1] |

The Gay Divorcee is a 1934 American musical romantic comedy film directed by Mark Sandrich and starring Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers.[2] It also features Alice Brady, Edward Everett Horton, Erik Rhodes, and Eric Blore. The screenplay was written by George Marion Jr., Dorothy Yost, and Edward Kaufman. It is based on the Broadway musical Gay Divorce, written by Dwight Taylor, with Kenneth Webb and Samuel Hoffenstein[3] adapting an unproduced play by J. Hartley Manners.[4]

The stage version included many songs by Cole Porter that were left out of the film, except for "Night and Day". Although most of the songs were replaced, the screenplay kept the original plot of the stage version. Three members of the play's original cast repeated their stage roles: Astaire, Rhodes and Blore.[5]

The Gay Divorcee was the second (after Flying Down to Rio) of ten pairings of Astaire and Rogers on film and their first one as a duo in leading roles.[2]

Plot

[edit]

Guy Holden, a famous American dancer, is at a Paris nightclub with his friend, scatterbrained English lawyer Egbert Fitzgerald, when they both realize that they have forgotten their wallets. After Guy dances for the audience to avoid washing dishes to work off the bill, Egbert discovers his wallet in a different pocket.

Traveling to England by ship, Guy encounters Mimi Glossop, whose dress has been caught when closing a trunk, asking Guy to call a porter to open the trunk to free her. Taking advantage of the situation, Guy teases her and attempts to free her dress, but ends up tearing the skirt at thigh level, angering Mimi. Chastised, Guy apologizes and gives Mimi his coat to cover up, and asks for her address to retrieve his coat, but Mimi insists that she will mail it back at the address he provides.

Mimi returns the coat, paying the courier not to disclose her contact information. After searching for Mimi in London for two weeks, Guy ends up serendipitously rear-ending her car in traffic. As Mimi drives away and races to evade him, he chases her into the country. Taking a shortcut, Guy sets up a fake roadblock, trapping her, offering her an impromptu picnic and casually proposing marriage. Convinced that he is insane, she rebuffs his attempts to charm her and attempts to tear up notes with his phone number (but keeps one), but he learns that her name is Mimi.

Coincidentally, Mimi seeks a divorce from her geologist husband, Cyril Glossop, who she has not seen for some time. Under the guidance of her domineering and much-married Aunt Hortense, she consults bumbling lawyer Egbert Fitzgerald, once a fiancé of her aunt. He arranges for Mimi to spend a night at a seaside hotel in Brightbourne and to be caught flagrante delicto in a staged "adulterous relationship", a purpose for which he hires a professional co-respondent, Rodolfo Tonetti. In an unrelated previous conversation with Guy, Egbert had been impressed when Guy philosophically used the phrase, "Chance is the fool's name for fate". Without Guy's knowledge and without intending any connection, Egbert gives Mimi the expression as a code phrase to identify her co-respondent.

Accompanying his friend Egbert to the hotel, the besotted and unaware Guy encounters Mimi, who has warmed up to him, and admits that she attempted to contact the phone number that he gave her. He sings Cole Porter's "Night and Day" to her, and they fall under a spell while dancing together. Wanting to impress Mimi, Guy waxes philosophical, inadvertently using the code phrase that Egbert has given Mimi to identify the co-respondent. Appalled, Mimi mistakes him for the co-respondent who she has been expecting, considering him not much more than a gigolo.

When Mimi gives Guy her room number and makes it clear that she expects him "at midnight", Guy is astonished by her seemingly brazen attitude. Guy keeps the "appointment" in Mimi's bedroom, and Tonetti arrives, revealing the truth and clearing up the misunderstandings. Not trusting Tonetti alone with Mimi, Guy insists on staying, potentially thwarting the point of a co-respondent for Mimi's divorce case. Tonetti insists that Mimi and Guy not foil the plan by being seen together outside of the bedroom. While Tonetti is busy playing solitaire in another room, Guy and Mimi contrive to escape and dance the night away. An elaborate 16-minute dance sequence, "The Continental", follows, with Mimi singing the introduction, another singer and ensembles of dancers doing routines, and Guy and Mimi joining in.

In the morning, after several mistakes with the waiter, Guy hides in the next room when Cyril arrives at the door, while Mimi and Tonetti pretend that they are lovers. When Cyril does not believe that Mimi would fall for Tonetti, Guy comes out and embraces Mimi in an attempt to convince Cyril that he is her lover, but to no avail. Cyril does not want a divorce from a wealthy wife. The unwitting waiter ultimately reveals that Cyril is an adulterer, having come to another hotel on previous occasions with another woman, thus clearing the way for Mimi to obtain a divorce and marry Guy.

Cast

[edit]- Fred Astaire as Guy Holden

- Ginger Rogers as Mimi

- Alice Brady as Hortense

- Edward Everett Horton as Egbert

- Erik Rhodes as Tonetti

- Eric Blore as the waiter

- William Austin as Cyril Glossop

- Charles Coleman as the valet

- Lillian Miles as guest

- Betty Grable as guest

Songs and dance numbers

[edit]New songs introduced in the film

- "The Continental" (lyrics: Herb Magidson; music: Con Conrad) won the first Academy Award for Best Original Song for its elaboration in the more-than-16-minute song-and-dance sequence toward the end of the film, as sung by Rogers, Erik Rhodes and Lillian Miles, and danced by Rogers, Astaire and ensemble performers. Arthur Fiedler and the Boston Pops Orchestra recorded the music in their first RCA Victor recording session, in Boston's Symphony Hall, July 1, 1935.

- "Don't Let It Bother You" (lyrics: Mack Gordon; music: Harry Revel), the film's opening number, sung by chorus, danced by Astaire.

- "Let's K-nock K-nees" (lyrics: Mack Gordon; music: Harry Revel) at the beach resort, sung by Betty Grable, with talking verses vocalized by Edward Everett Horton, danced by Grable, Horton and chorus.

- "A Needle in a Haystack" (lyrics: Herb Magidson; music: Con Conrad), sung and danced by Astaire.

Other songs

- "Night and Day" (Cole Porter), sung by Astaire, danced by Rogers and Astaire in a hotel suite overlooking an English Channel beach at night. It was their first romantic dance duet in film.[6] Dance critic Alastair Macaulay wrote that this movie, and this dance number in particular, created one of the archetypes of romance, and that cinema "has never had another couple who enshrined romantic love so definitively in terms of dance."[7]

Production

[edit]Development

[edit]After the success of Astaire and Rogers's first feature, Flying Down to Rio (1933), RKO's head of production, Pandro S. Berman, purchased the screen rights to Dwight Taylor's Broadway musical Gay Divorce, with another Astaire and Rogers matchup in mind. According to Astaire's autobiography, director Mark Sandrich claimed that RKO altered the title to insinuate that the film concerned the amorous adventures of a recently divorced woman (divorcée).[8] In addition to the credited screenwriters, Robert Benchley, H. W. Hanemann, and Stanley Rauh made uncredited contributions to the dialogue.

Dance routines from the film, specifically "Night and Day" and the scene in which Astaire dances on the table, were taken from Astaire's performances in the original play, Gay Divorce.[8] The choreography to "Don't Let It Bother You" came from foolhardy antics during rehearsals, and became an in-joke in future Astaire–Rogers films.[9]

Filming

[edit]Exteriors set in what was supposed to be the English countryside were shot in Clear Lake, California. Additional exteriors were filmed in Santa Monica and Santa Barbara, California.[8]

The car driven by Rogers was her own, a 1929 Duesenberg Model J. It still exists, and has been displayed at least once at the Amelia Island Car Show, Concours d'Elegance.[10]

Censorship concerns

[edit]James Wingate, Director of Studio Relations for RKO, warned: "Considering the delicate nature of the subject upon which this script is based... great care should be taken in the scenes dealing with Mimi's lingerie, and... no intimate article should be used." Wingate also insisted that no actor or actress appear in only pajamas.[8]

There are differing accounts of why the film's name was changed from the play's Gay Divorce to The Gay Divorcee. In one, the Hays Office insisted that RKO change the name, finding it "too frivolous toward marriage": while a divorcée could be gay or lighthearted, it would be unseemly to allow a divorce to appear so.[11] According to Astaire, however, the change was made proactively by RKO. Sandrich told him that The Gay Divorcee was selected as the new name because the studio "thought it was a more attractive-sounding title, centered around a girl".[12] RKO even offered $50 to any employee who could come up with a better title.[8] In the United Kingdom, the film was released under the title The Gay Divorce.[8][13]

Reception

[edit]Box office

[edit]According to RKO records, the film earned $1,077,000 in the United States and Canada, and $697,000 elsewhere, resulting in a profit of $584,000.[1]

Critical response

[edit]The New York Times critic Andre Sennwald said of the film on November 16, 1934: "Like the carefree team of Rogers and Astaire, The Gay Divorcee is gay in its mood and smart in its approach. For subsidiary humor, there are Alice Brady as the talkative aunt; Edward Everett Horton as the confused lawyer ... and Erik Rhodes ... as the excitable co-respondent, who takes the correct pride in his craftsmanship and objects to outside interference. All of them plus the Continental, help to make the new Music Hall show the source of a good deal of innocent merriment."[14]

Accolades

[edit]The film was nominated for the following Academy Awards, winning in the category Music (Song):[15]

- Best Picture (Nominated)

- Art Direction (Van Nest Polglase, Carroll Clark) (Nominated)

- Music (Scoring) (Max Steiner) (Nominated)

- Music (Song) – "The Continental" (Won) – the first winner of this award; it won against "Carioca", from the previous Astaire–Rogers film, Flying Down to Rio[16]

- Sound Recording (Carl Dreher) (Nominated)

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Jewel, Richard B. (1994). "RKO Film Grosses, 1929–1951: the C. J. Tevlin ledger". Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television. 14 (1): 55. doi:10.1080/01439689400260031. ISSN 0143-9685.

- ^ a b "Ginger Rogers & Fred Astaire 2: The Gay Divorcee (1934)". Reel Classics. December 16, 2008. Archived from the original on July 6, 2016. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ "The Gay Divorcee (1934) – Screenplay Info". Turner Classic Movies. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016.

- ^ "Gay Divorce – Broadway Musical – Original". Internet Broadway Database.

- ^ Connema, Richard (April 29, 2007). "Cole Porter's Very Seldom Seen 1932 musical Gay Divorce". Talkin' Broadway. Archived from the original on November 25, 2015. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ Hyam, Hannah (2007). Fred and Ginger: The Astaire–Rogers Partnership 1934–1938. Pen Press. pp. 107–108, 192, 200. ISBN 978-1-905621-96-5.

- ^ Macaulay, Alastair (August 14, 2009). "They Seem to Find the Happiness They Seek". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 27, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f "The Gay Divorcee (1934)". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Retrieved July 8, 2024.

- ^ "The Gay Divorcee (1934) – Trivia". Turner Classic Movies. Archived from the original on December 20, 2016. Retrieved December 16, 2016.

- ^ Raustin (December 20, 2011). "Ginger Rogers' 1929 Duesenberg stars at 2012 Amelia Island". Old Cars Weekly.

- ^ Sarris, Andrew (1998). "You Ain't Heard Nothin' Yet": The American Talking Film, History & Memory, 1927–1949. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-19-513426-1.

- ^ Astaire, Fred (1981). Steps in Time: An Autobiography. New York: Da Capo Press. p. 198. ISBN 978-0-306-80141-9.

- ^ Halliwell, Leslie (1981). Halliwell's Film Guide (3rd ed.). London: Granada. p. 375. ISBN 978-0-246-11533-1.

- ^ A. S. (November 16, 1934). "'The Gay Divorcee,' With Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers, at the Music Hall – 'Redhead.'". The New York Times. ProQuest 101148306. Retrieved July 8, 2024.

- ^ "The 7th Academy Awards | 1935". Academy Awards. Retrieved August 7, 2011.

- ^ Mankiewicz, Ben (June 7, 2016). Outro to the Turner Classic Movies showing of The Gay Divorcee.

External links

[edit]- 1934 films

- 1934 musical comedy films

- 1934 romantic comedy films

- 1930s American films

- 1930s English-language films

- 1930s romantic musical films

- 1930s screwball comedy films

- American black-and-white films

- American films based on plays

- American musical comedy films

- American romantic comedy films

- American romantic musical films

- American screwball comedy films

- Films about divorce

- Films based on musicals

- Films directed by Mark Sandrich

- Films produced by Pandro S. Berman

- Films scored by Cole Porter

- Films scored by Max Steiner

- Films set in East Sussex

- Films set in hotels

- Films set in London

- Films shot in Santa Monica, California

- Films that won the Best Original Song Academy Award

- Films with screenplays by Dorothy Yost

- RKO Pictures films

- English-language romantic comedy films

- English-language romantic musical films

- English-language musical comedy films